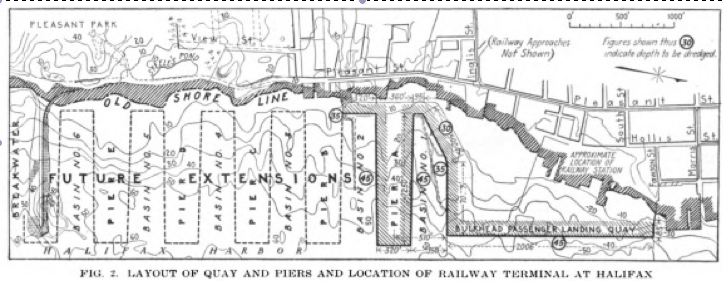

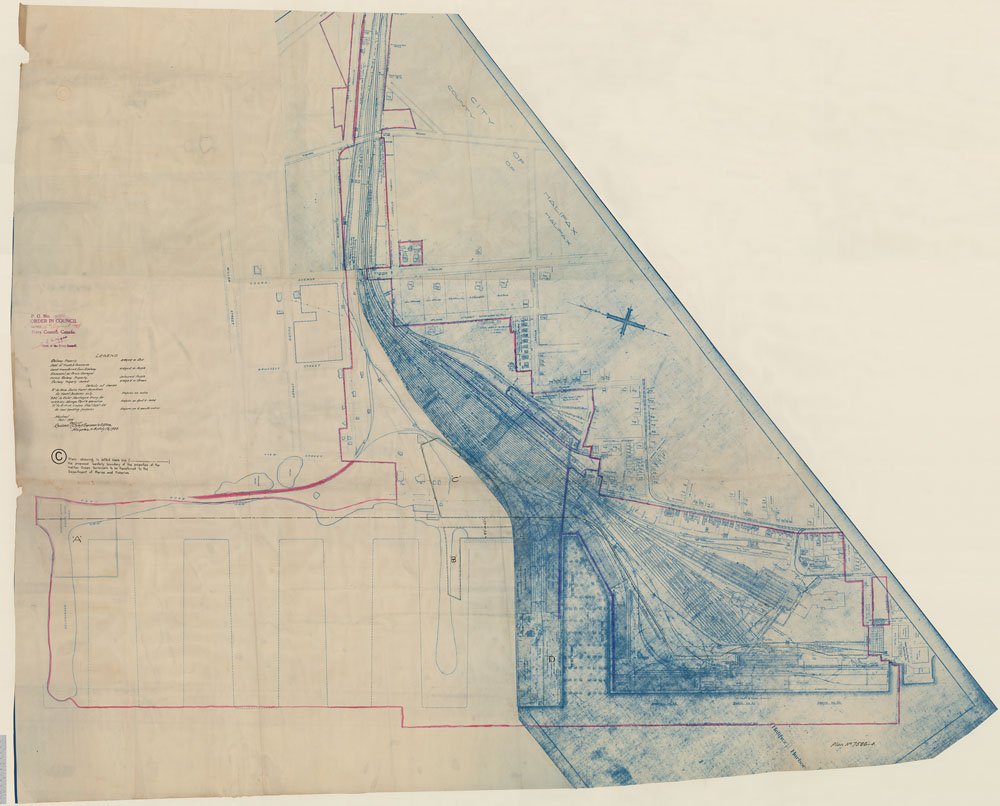

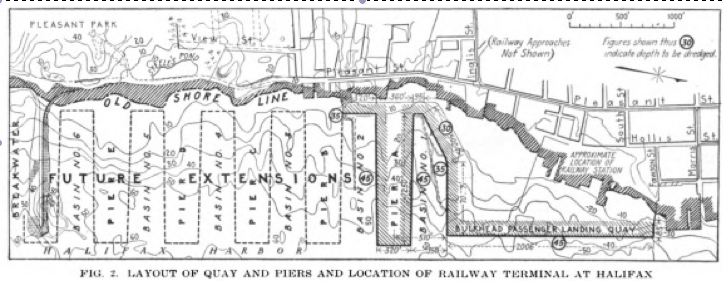

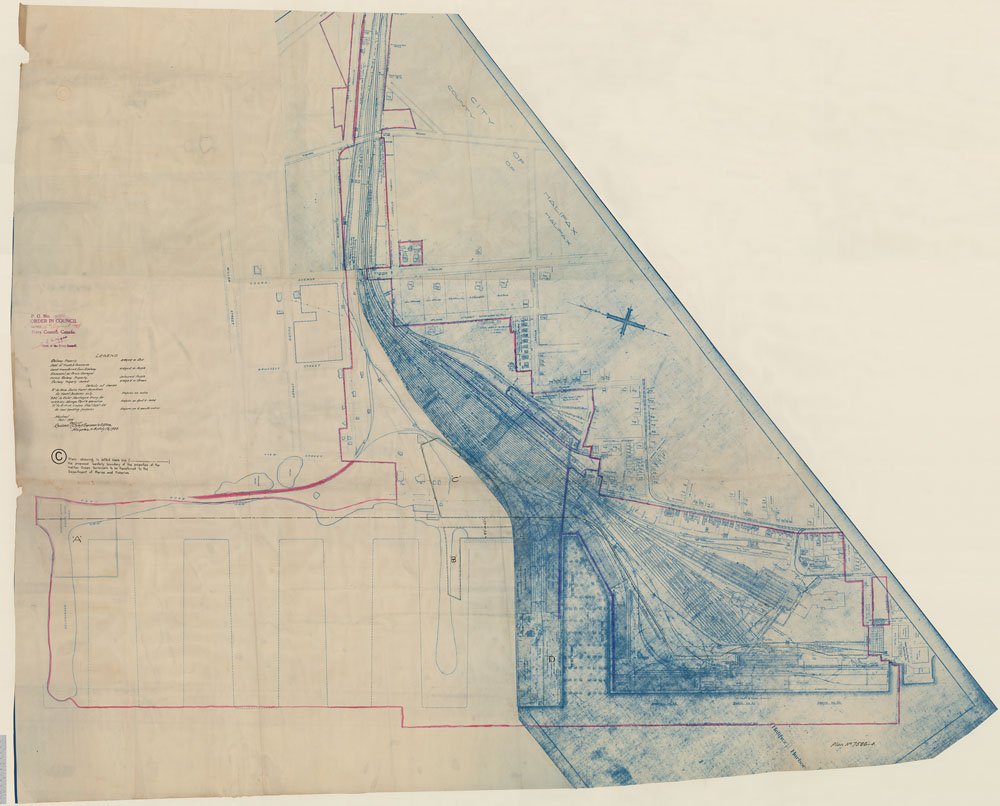

The Ocean Terminals were built in the south end of the city, close to the mouth of the harbour, and were meant to be new, modern and larger port facilities for Halifax. It was quite the civil engineering feat. The project was for the construction of what we know today as Piers 20-28, the railway cut, and port facilities, and the South end Stion and hotel Complex.

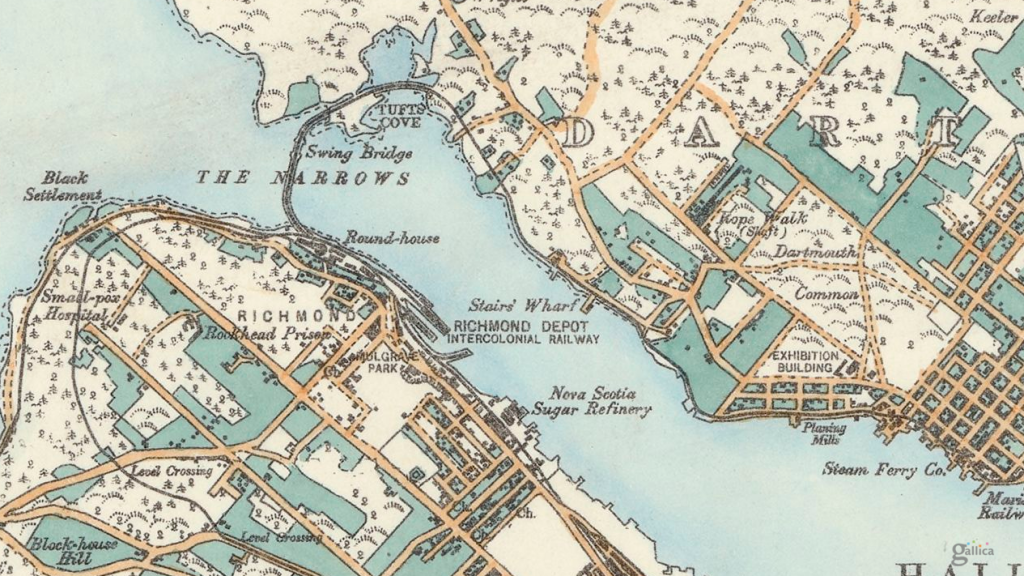

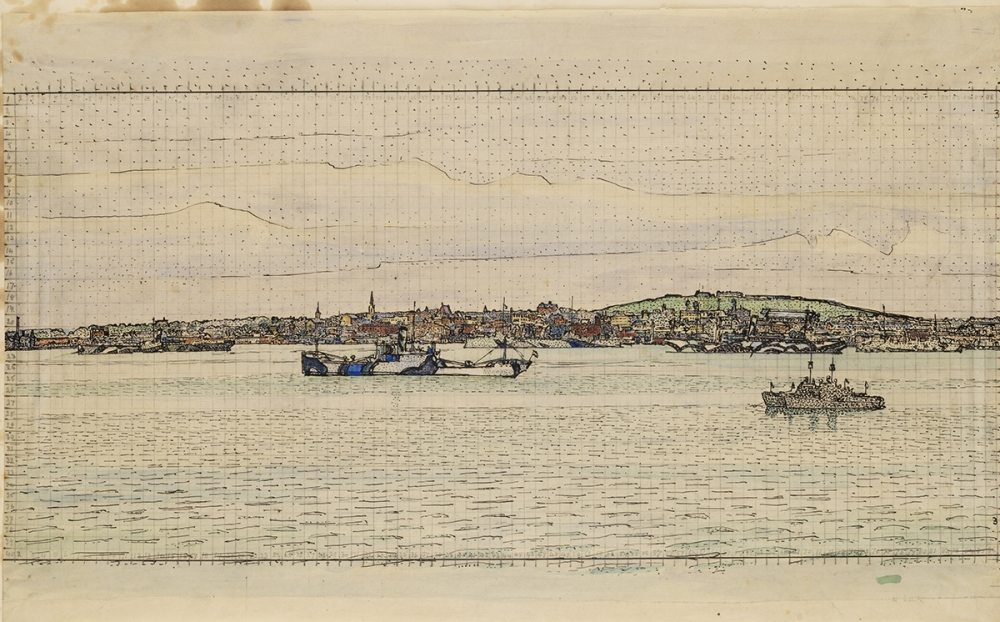

Halifax for a while dominated as Canada’s East Coast port, but poor railway access made it too distant; and antiquated methods, unprofitable. In 1910, improvements were made to Pier 2 at the deep water terminus in the north end, however it was constrained by space available to it. Wharves, private residences and businesses had encroached, and there was no longer space for railway expansion. In 1912, the Dominion Government decided to proceed with the Ocean Terminals project.

Halifax for a while dominated as Canada’s East Coast port, but poor railway access made it too distant; and antiquated methods, unprofitable. In 1910, improvements were made to Pier 2 at the deep water terminus in the north end, however it was constrained by space available to it. Wharves, private residences and businesses had encroached, and there was no longer space for railway expansion. In 1912, the Dominion Government decided to proceed with the Ocean Terminals project.

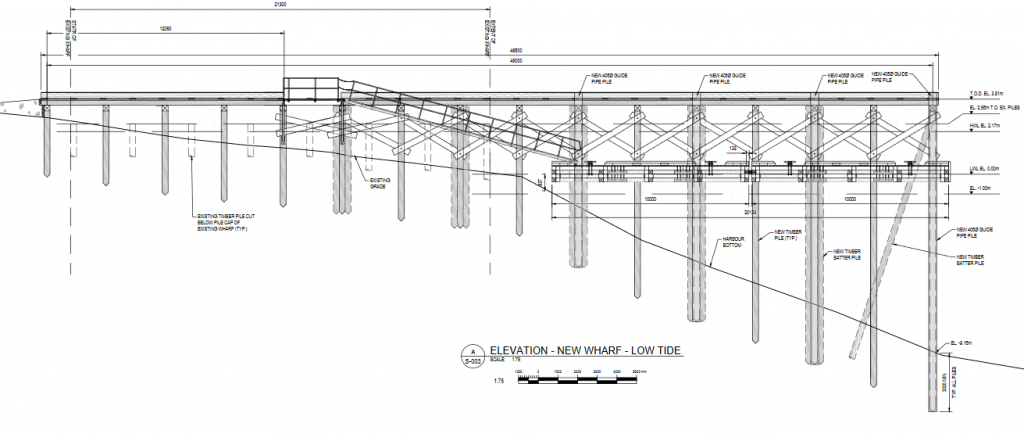

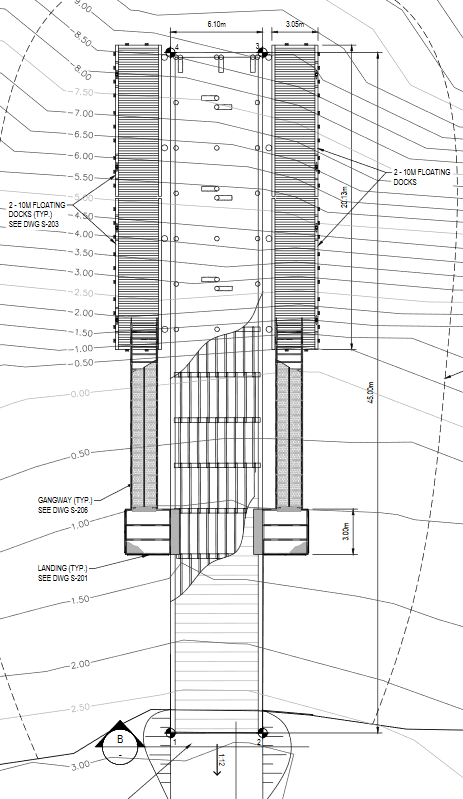

Though expected to be much larger, the initial project called for the construction of the passenger terminal, interconnected with the rail terminal, as well as Pier A, and the breakwater. The requirements were for 45′ depth.

The construction contract was held by Foley Bros, Welsh, Stewart & Fauquier. James Macgregor was the Superintending Engineer, responsible for design and construction for the Canadian Government.

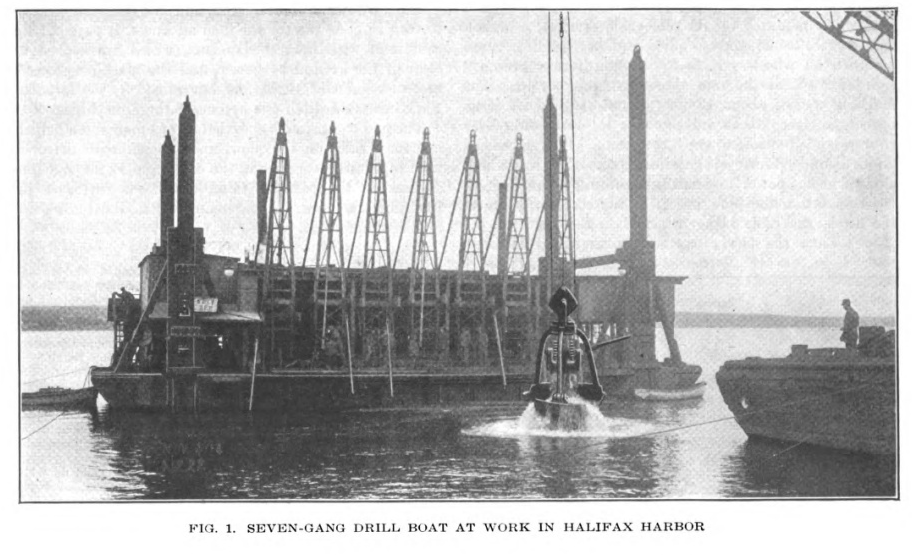

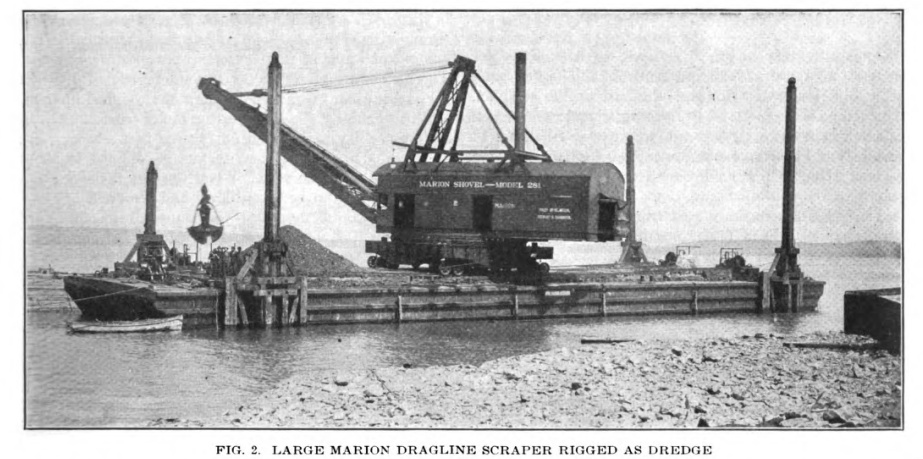

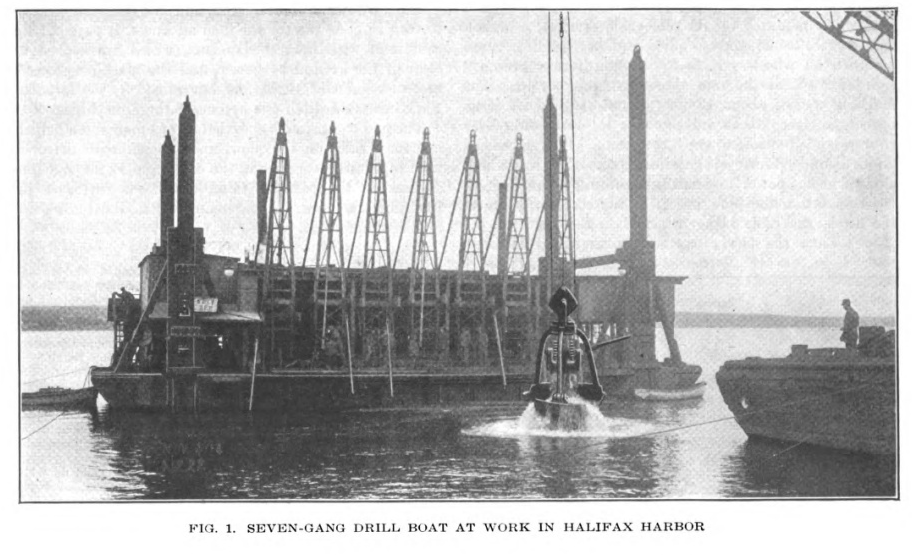

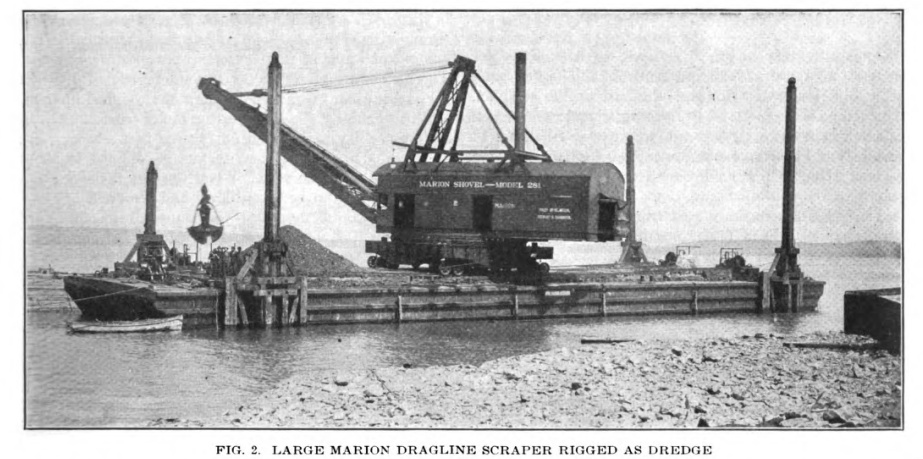

Though Halifax is known for having a deep natural channel, the piers were located close to shore; in places, in as little as 10 feet of water, and so required substantial dredging. 250,000 cubic yards of material was removed to ensure the required 45′ depth was met. As well, stable foundations would be required for the piers. The area would be drilled, charges set, and then the rock excavated. Most of the rock was excavated by the Canadian government’s 12yd dipper dredge “Cynthia”, though deeper areas were done with a Marion Dragline scraper on a barge fitted with an orange peel bucket. This crane was intended to be used for block placement, but proved versatile.

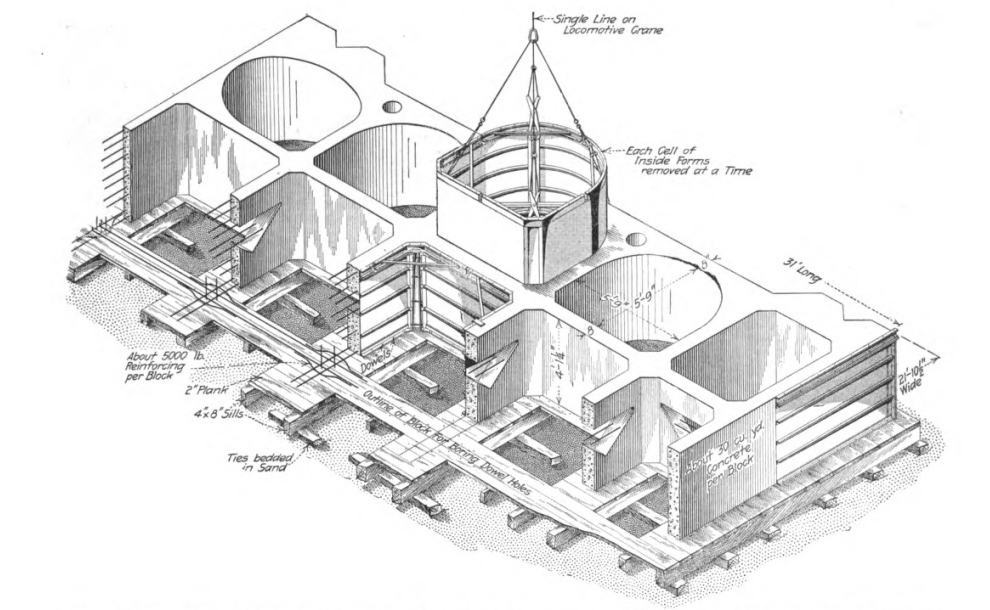

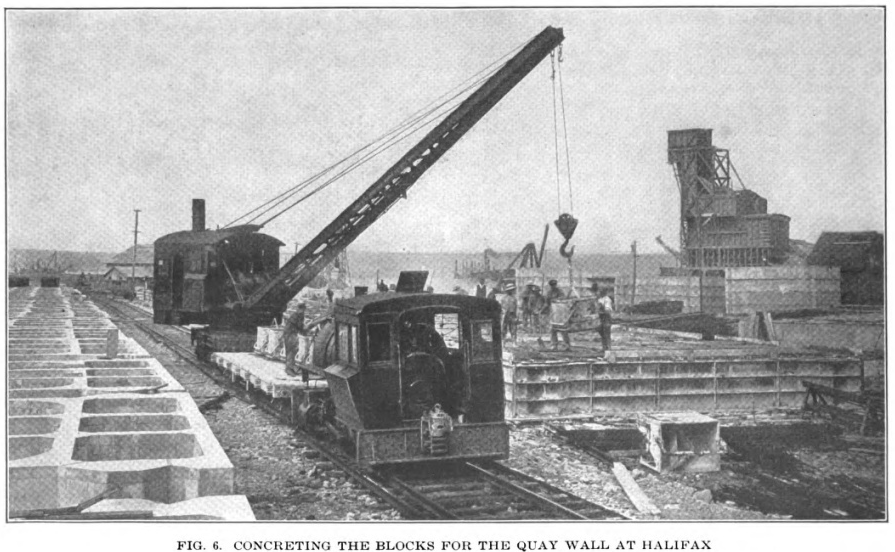

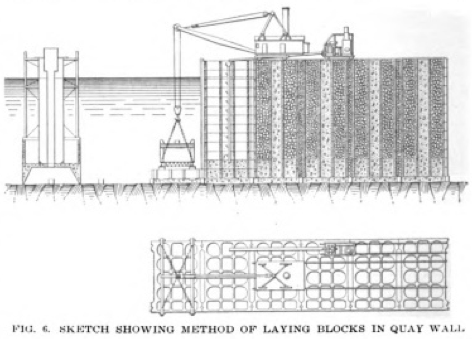

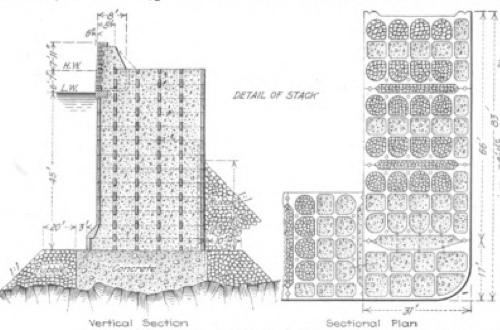

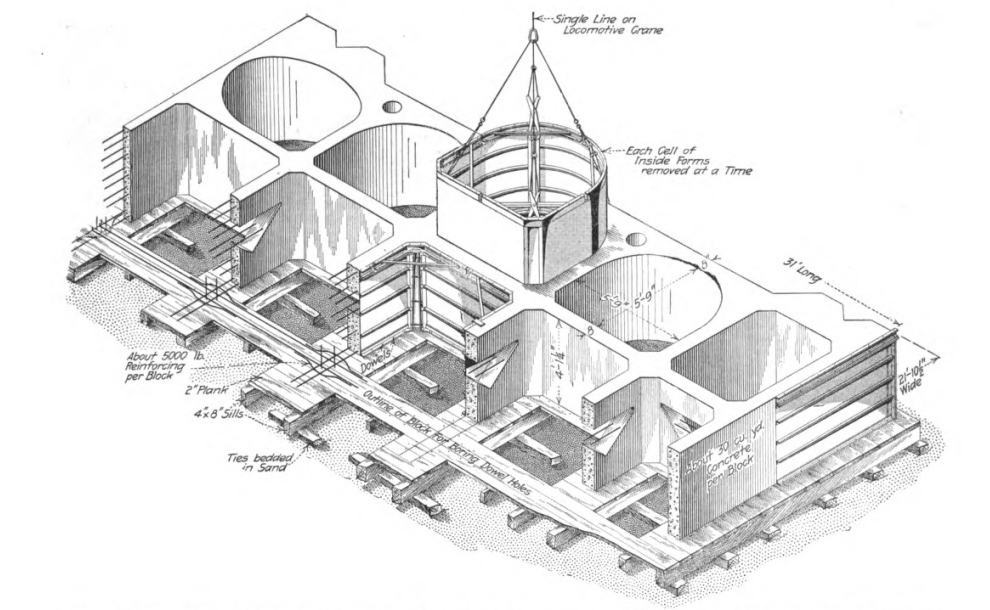

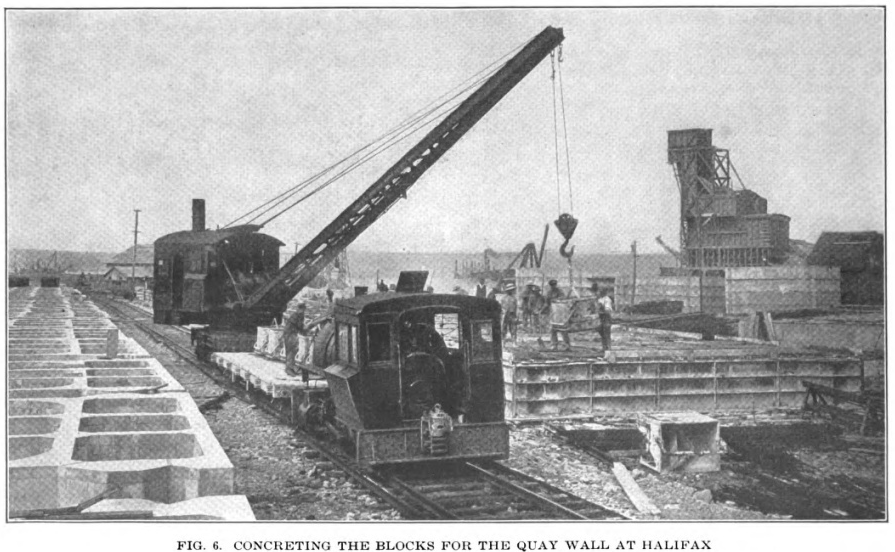

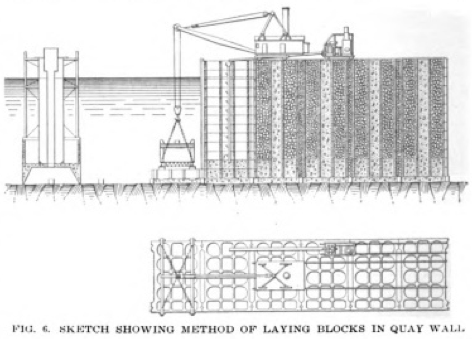

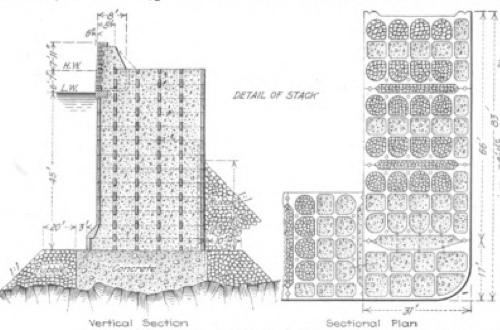

The pier was to be constructed from 3647 sixty-ton Concrete blocks would then be stacked to form the pier face, and then after placement filled with sand rocks and concrete. The area within would then be filled. The blocks were 31′ wide, 22’long and 4’tall. They were cast on site, and stored until they were required to be placed. Though this method was not new, it was to date the largest construction using this method.

A concrete batch plant was setup on site, and the blocks were produced using a forming system. Most of the blocks were identical, so they could be easily mass produced.

A concrete batch plant was setup on site, and the blocks were produced using a forming system. Most of the blocks were identical, so they could be easily mass produced.

The blocks were cast on site and stored until needed. When they were required, a 100ton crane would pick up the block, take it to the end of the pier and lower it into place. the blocks were cast with keys to ensure they aligned properly when placed.

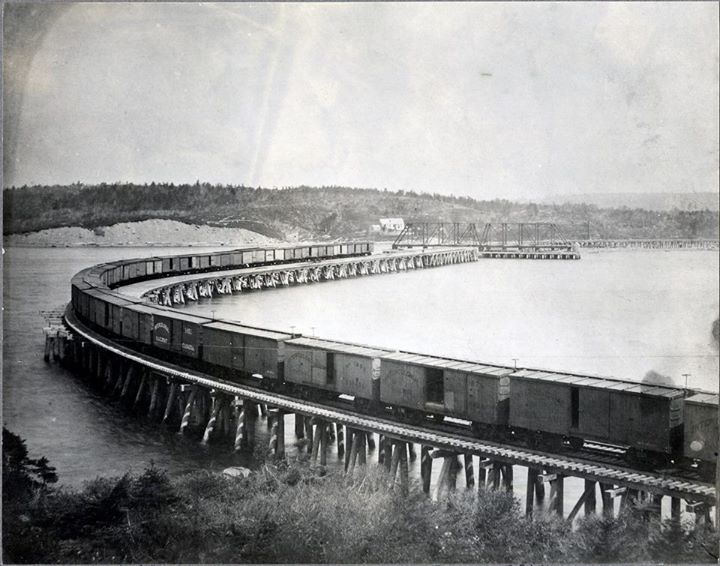

The breakwater was constructed with rock removed from the railcut. Loads of rock would be pushed out on railcars to the end of the breakwater, then across a plate girder bridge, and onto a barge. They would then be dumped. The barge was kept level in the tides by adjusting ballast. As the pier extended, the barge would be moved further along until the required 1500′ was constructed.

Once the piers were built, additional Facilities could be constructed. Pier A featured a sizeable freight shed. Due to the Ongoing war, the initial shed was constructed from timber. due to the need for it, and available materials.

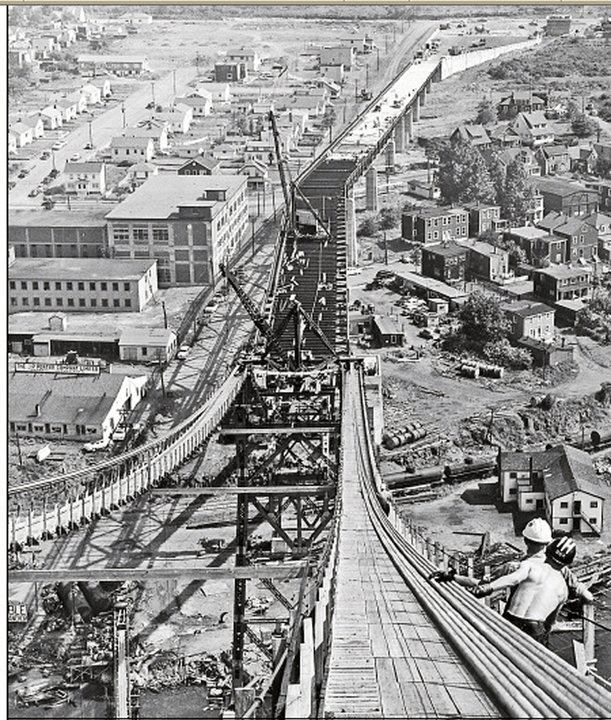

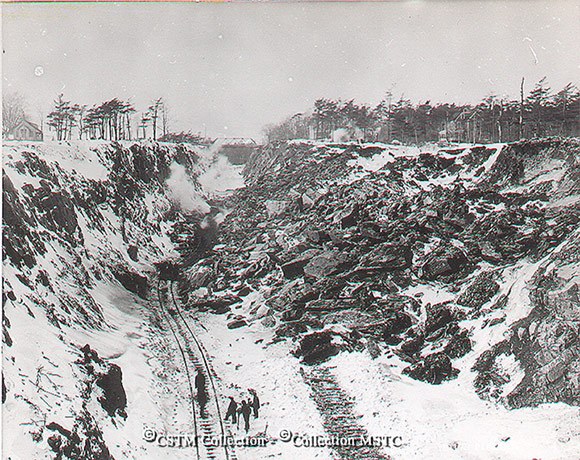

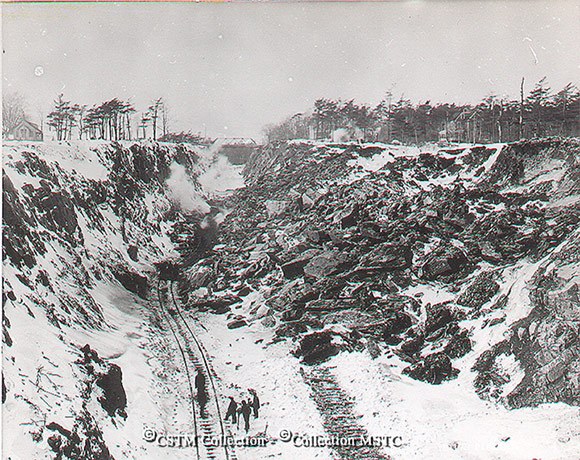

Along with the Improved Piers, Improved rail facilities were constructed as part of the Project. It took the railway from Three Mile House at Fairview, around behind the city to the south end to serve the new ocean terminals and railway station. It also included construction of the Bedford Basin Yard. The cut is approximately 6 miles long and, as built, double track to the terminal where it expands to 4 tracks.

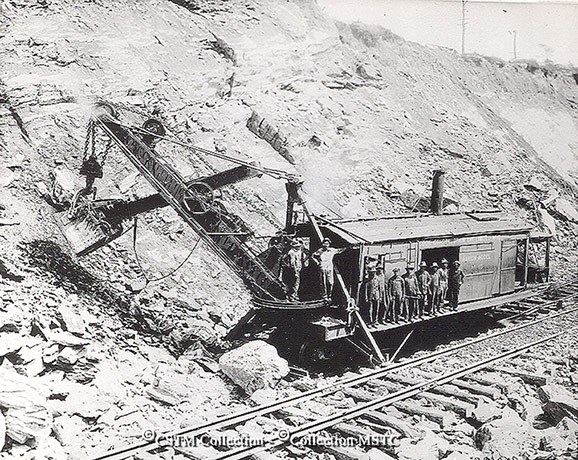

Construction was the responsibility of Cook Construction Co & Wheaton Bros. They were tasked with excavating the 2.5 million cubic yards of material that needed to be removed for the cut. It was mostly rock. In the south end, material was used to make up the breakwater. At the north end, excavated material was used to build the Rockingham yard, located in front of St Vincents College. (Now Mount St Vincent University.) Three Mile House itself was demolished in 1918.

Initially there were problems drilling the rock, due to the seams running through it, however electric Cyclone type well drills proved to be successful. Drilling occurred in advance of the shovel operations, holes were capped to await blasting, and each blast was done to a maximum depth of 30′, across the width of the cut in 100-200′ long sections.

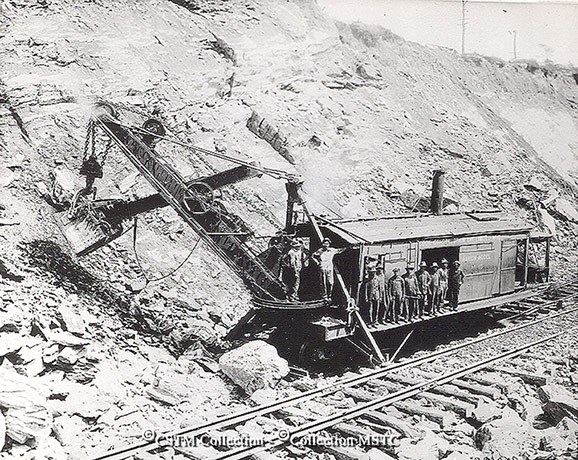

Two Bucyrus 100 ton shovels were used, as well as two Bucyrus 70 ton shovels, and 2 Marion 60 ton shovels. Rocks too large to be loaded were broken up with drills located on the shovels. Similar equipment to this was also used to dig the Panama Canal. Both Marion and Bucyrus were Ohio-based companies, and Marion was eventually acquired by Bucyrus. Bucyrus became part of Caterpillar in 2011, and forms the base of their mining equipment division.

Though the rail cut avoided the major population in Halifax, it had a major impact on the grand estates in the south and west ends of the peninsula. Properties needed to be expropriated, and many houses were demolished, included Samuel Cunard’s Oaklands estate. The expropriations caused many large lots to be subdivided and eventually led to the expansion of middle class Halifax into these areas.

Though the rail cut avoided the major population in Halifax, it had a major impact on the grand estates in the south and west ends of the peninsula. Properties needed to be expropriated, and many houses were demolished, included Samuel Cunard’s Oaklands estate. The expropriations caused many large lots to be subdivided and eventually led to the expansion of middle class Halifax into these areas.

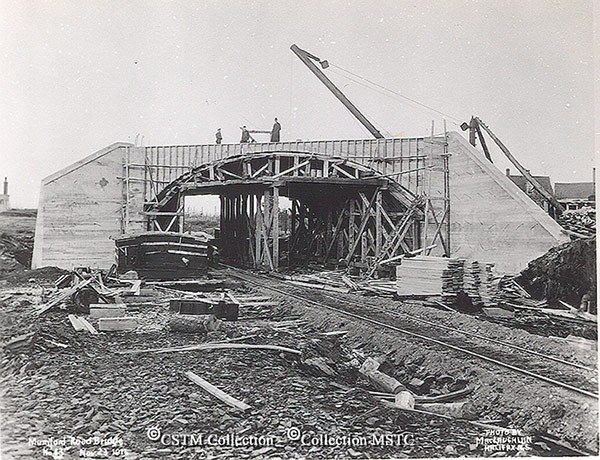

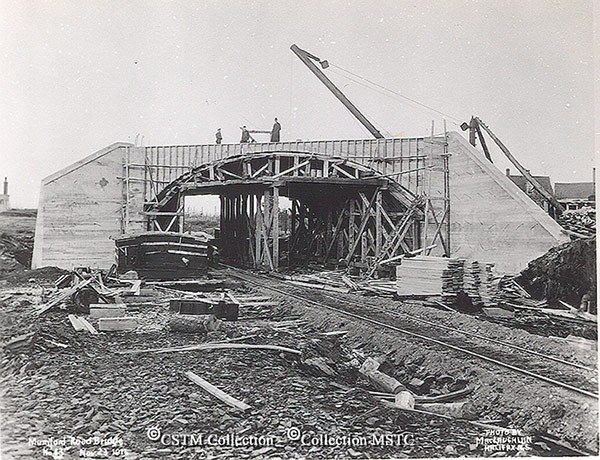

During construction, roads were interrupted and temporary bridges put in place (left), before the grand concrete arch bridges could be constructed, the most visible of these being Young Avenue at the mouth of the rail cut. The example under construction below is believed to be Mumford Road.

The Rockingham yard under construction. The 2 tracks in the foreground are the mainline, and the train is dumping fill.

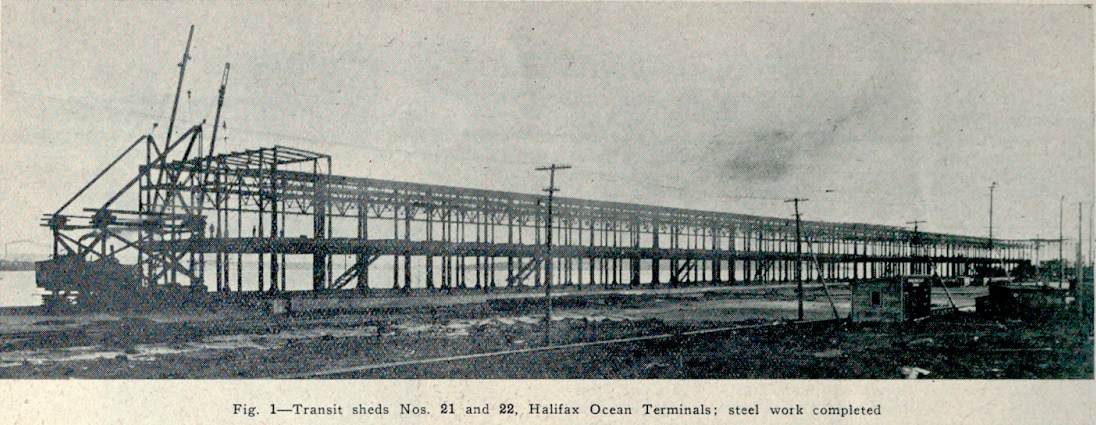

the Transit Sheds of Piers 20-22 were constructed in the Early 20’s. The Contract Record of March 24 1920 reported that Sheds 21 and 22 had the steelwork erected in 6 weeks with use of a Traveling Derrick by the Dominion Bridge Company. the Steel work was manufactured in the US, however wartime shortages delayed construction.

the Grain handling facilities were intended from the beginning, and the elevator was installed by 1926.

Built in 1928, the train station and Hotel Nova Scotian were the final pieces of the port improvement project.

The images above are aerial views from 1931, and are from The Richard McCully Aerial Photograph Collection at the NS Archives. The current train station replaced a temporary one built in 1918 to coincide with the opening of the railcut and ocean terminals. The temporary station was required as the Intercolonial Railway Station at the foot of North Street had been destroyed in the Halifax Explosion of 1917, and can be seen in front of the train shed.

The Station and Hotel were designed by John Smith Archibald in association with John Schofield. Archibald owned his own practice, whereas Schofield worked for the Railway. The two did a number of commissions for CN Railways, including expanding the Chateau Laurier in Ottawa. Archibald had a wide and Varied career, designed numerous homes, schools, hospitals and hotels, and also has the distinction of having designed the Montreal Forum.

The Halifax railway complex also included Cornwallis Park, which opened in 1931. Archibald was a proponent of the City beautiful movement, which sought to impose order in cities to reduce crime and poverty. The particular architectural style of the movement borrowed mainly from the contemporary Beaux-Arts and neoclassical styles, which emphasized the necessity of order, dignity, and harmony. you can note, that in the photos the central axis of the park is aligned with the main entry of the Nova Scotian Hotel. the Now controversial statue of Cornwallis was also installed by the railway – the park lands were water sold to the city of Halifax.

The Railway Station, was constructed with a modern steel frame, truss joists, with brick & stone facing Exterior. It cost $571,939.19 to build. The Hotel featured 168 rooms when built, and is also of steel construction. It’s construction cost was $1,658,456 – both in 1928 dollars.

The Station also included a direct connection to Pier 21 to Facilitate movement of people from ships to train. the final images bellow from 1934 show the extent of the completed project.

Note: A version of this post Previously appeared on my other blog Builthalifax